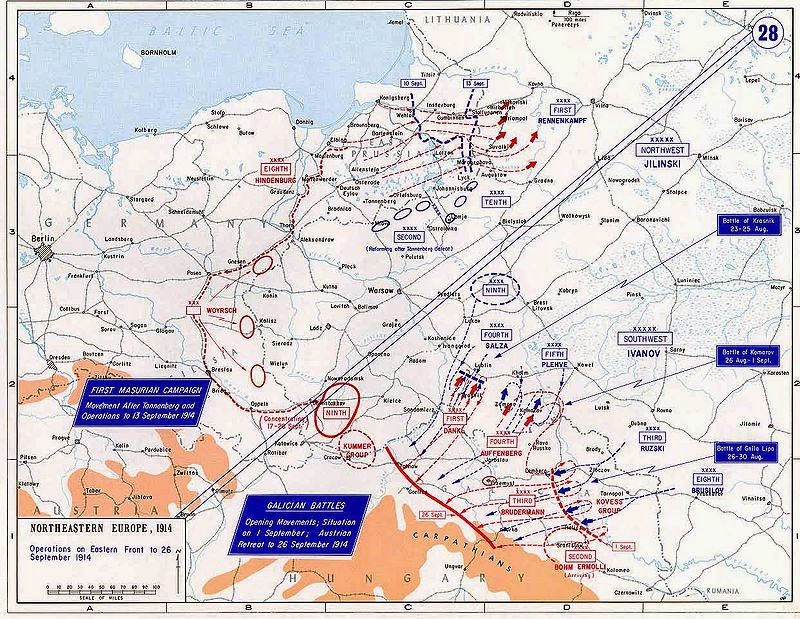

By mid September, the biggest actions of

the war had been completed – Battles of the Frontiers and the Marne in the

west, and Lemberg and Tannenberg in the east - and a stalemate was developing

on both main fronts. All sides paused before the next phases of major actions

(See posts on Race to the Sea and Ypres 1 in the west).

The neutrals were influenced by the Central

Powers’ reverses at the Marne and Lemberg – Roumania stayed neutral, and Italy

kept out. Falkenhayn was determined to continue his modification of the

Schlieffen plan to take control of Belgium and the Channel coast, but faced a

major problem in the East, where Germany feared the crushed Austrians might have been about to

make a separate peace. He ordered Hindenberg and Ludendorff to reinforce

Austria on its northern front, and they sent 250,000 men from East Prussia as a

new German 9th Army, which effectively became Austria's central army of three. They faced Russian armies across a 100 mile front that would see complex actions through the winter.

The Russians were keen to invade southern Poland, and were urged to do so by the French. The Russian Grand Duke regrouped into a strong N-S line on the line of the Vistula. This involved moving a lot of his forces to the north, and he was unaware of the southern movement of the German 9th. However, he was confident that he well placed whether needing to attack or defend from his new line. At the same time, the German success in the north had the Russians on the back foot, and enabled them to move into Russian territory near the Baltic, and to consider moving south to take Warsaw.

|

| Grand Duke Nicholas 1856-1929 |

The Russians were keen to invade southern Poland, and were urged to do so by the French. The Russian Grand Duke regrouped into a strong N-S line on the line of the Vistula. This involved moving a lot of his forces to the north, and he was unaware of the southern movement of the German 9th. However, he was confident that he well placed whether needing to attack or defend from his new line. At the same time, the German success in the north had the Russians on the back foot, and enabled them to move into Russian territory near the Baltic, and to consider moving south to take Warsaw.

Falkenhayn knew he could only re-deploy sufficient numbers for a

strategic defence on the Eastern front because of his need to strike decisively in Belgium. From the outset Russia held an essentially

attacking strategy towards Germany, and despite its heavy defeat in Prussia at

Tannenberg, still intended to push through Galicia and into Silesia. Their commander-in-chief, the Grand Duke Nicholas, was keen to make this break before winter

conditions set in. If he could break through to the line of the Oder, he would

threaten both Berlin and Vienna; and would also take control the oil wells of

Galicia.

On their extreme left, this wing of the Russian armies could pushing through the eastern Carpathian passes to enter into north Hungarian plains, and further threaten the Austrian armies. Hungarian defences were weak, since they had suffered terribly at Lemberg, and most of their remaining forces were under siege in Przemysl, or in full retreat towards Cracow. The Russians wanted to control the two main Galician fortresses at Jaroslav amd Przemysl, and the Austrian were desperate to hold on to them, since they guarded the main railways and transport links west to Cracow, and south into Hungary. Jaroslav fell by 23rd September, and by the same date Przemysl was surrounded, although it held out under siege. Dmitrieff, the Russian general, preferred to starve them rather than lose men in storming the garrison. Meanwhile Ivanov had stormed ahead to the west and on 29th his cavalry reached Dembica, around 100 miles east of Cracow, having crossed the River San in large numbers and in numerous places. It was at this time they learned of the German moves southwards between Lowicz and Lodz, and Ivanov withdrew to the east of the San to conform with the Russian lines in the centre.

On their extreme left, this wing of the Russian armies could pushing through the eastern Carpathian passes to enter into north Hungarian plains, and further threaten the Austrian armies. Hungarian defences were weak, since they had suffered terribly at Lemberg, and most of their remaining forces were under siege in Przemysl, or in full retreat towards Cracow. The Russians wanted to control the two main Galician fortresses at Jaroslav amd Przemysl, and the Austrian were desperate to hold on to them, since they guarded the main railways and transport links west to Cracow, and south into Hungary. Jaroslav fell by 23rd September, and by the same date Przemysl was surrounded, although it held out under siege. Dmitrieff, the Russian general, preferred to starve them rather than lose men in storming the garrison. Meanwhile Ivanov had stormed ahead to the west and on 29th his cavalry reached Dembica, around 100 miles east of Cracow, having crossed the River San in large numbers and in numerous places. It was at this time they learned of the German moves southwards between Lowicz and Lodz, and Ivanov withdrew to the east of the San to conform with the Russian lines in the centre.

|

| Russian Artillery action in Galicia 1914 |

The Russian centre was aligned north and south covering Warsaw and the Polish salient, but the wings were quite disconnected. In the north, Rennenkampf’s army of the right wing was some hundreds of miles to the north east behind the line of the Niemen (today River Nemunas). Knowing that Germany would send reinforcements to rescue the Austrians in the south, the Russians were keen to lure Hindenberg into pursuit of Rennenkampf into Vilna province (today Lithuania), since it was strategically unimportant to them, and was very difficult terrain. Hindenberg’s pursuit had commenced on 7th September, advancing on a wide front towards the main Petrograd railway. Large parts of his force reached the Niemen by 21st September, but Rennenkampf had stationed all of his army in good defences on the Niemen's east bank. The river itself posed a formidable barrier in several battles that followed as Hindenberg attempted to cross in strength. The Russians lay in trenches on the low eastern shore, and waited until the Germans had built their pontoon bridges before blowing them to pieces. Hindenberg made a final great effort on 27th, following a full day of artillery bombardment, but with the same result, and a huge loss of troops. On 28th, he gave the order to retreat, realising that that this operation risked high loss for little strategic benefit. Retreat was difficult for the Germans, and they were severely harried, losing large numbers of troops in the Battle of the forest of Augustovo, but at least they avoided being encircled and made their escape. The Germans now realised they would have to move reinforcements to the south to prevent the other wing of the Russian armies breaking through to Cracow and beyond, since it had become clear they were going nowhere in the north.