|

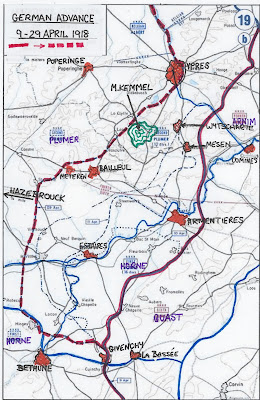

| 'Backs to the Wall" time. The alarming advance made by Operation Georgette. |

The end of the first week of Operation

Georgette saw both sides’ fate hanging in the balance. The Germans had to pause

to re-group and to supply their troops. For the British, Bethune and Hazebrouck

were still at risk, and the Germans were now pressurising the full range of Flanders hills west of

Ypres, from Mont des Cats behind Bailleul to Mount Kemmel. Not only Ypres, but the route to the coastal ports was opening.

It was at this stage, on 11th

April that the dour Haig, unable to persuade Foch to release more reserves from

further south, issued his most famous and Nelsonian order of the day: “There is no other course open to us but to

fight it out. Every position must be held to the last man; there must be no

retirement. With our backs to the wall, and believing in the justness of our

cause, each one of us must fight on to the end. The safety of our homes and the

freedom of mankind depend alike upon the conduct of each one of us at this

critical moment”. Things would get worse before they got better. On 14th

Bailleul fell, and on 16th so too did Wytschaete and Spanbroekmoelen.

By the 18th the Germans were ready to advance on Mount Kemmel from

the south and west. Success here would all but cut off Ypres, prompting an

Allied retreat to the channel, and necessitating flooding of the coastal plain.

Ludendorff’s revision of Georgette now had

two immediate objectives: the capture of Bethune, and the isolation of Ypres by

taking Mount Kemmel. Hazebrouck and a retreat to the coast would then follow as

a matter of course.

To increase the pressure on Ypres,

Ludendorff authorised Operation Tannenberg (an emotive choice recalling the

great pincer like German victory of 1914 see Post…). This was to be a huge movement

with Kemmel in the south, the coastal route in the north, and the beleaguered

Ypres caught in the pincers. The crucial engagements took place on 17th

and 18th April. Firstly the Belgian forces were successful in

rebuffing the coastal movement. Strong counter attacks rapidly reversed some

initial German gains, and the right hand pincer ground to a halt almost before

it had started. The left hand pincer was also rebuffed in several places, but

made sufficient progress to take the southern and western aspects of Kemmel,

and took all of Wytschaete. It was now able to overlook the remains of Ypres,

almost one year after it had been driven from the ridge.

South of the Lys, von Quast made his assault

towards Bethune along his whole section from Givenchy to Merville. To capture

Bethune he had to get across the La Bassée

canal. Despite reaching the eastern bank along much its length, his attempts

to cross all ended in costly failure. The defence put up by 4 Division of

Horne’s Army fully met the demands of Haig’s order of the day. Holding Givenchy proved the key to the defence of Bethune.

This was the beginning of the end of the

Battle of the Lys. The German machine had been comprehensively repulsed in the

north of Belgium, and severely damaged in its failure to cross the La Bassée

canal in front of Bethune. Only in the centre, at Mount Kemmel, could

Ludendorff hope to gain Ypres, and this would prove to be the final act of the

battle*. Sporadic action continued but for the next week both sides prepared for

this decisive moment. By now Foch was taking the lead on tactics, and he

brought in French reserve divisions to strengthen the Kemmel defences.

|

| The bleak view of Mount Kemmel in April 1918. Hardly Himalayan, but at 500 feet, it dominated the views over Ypres and to the coast |

The

attack came on 25th April, following an opening bombardment from

Meeteren (west of Kemmel) to the Ypres-Comine canal. The fighting of the next

four days matched any of the war for its fierceness, with thousands of British,

French and German casualties. As in OM, the Germans almost made all of their

objectives, but fell just short before losing ground to counter-attacks. They

did reach the highest point of Kemmel, and the road from Ypres to Poperinge

but, exhausted, by the end of April they were contained by Allied

reinforcements. A final attempt to break through on the coastal route north of

Ypres had again been successfully beaten off by the Belgian forces. By the end

of May, Ludendorff’s focus had shifted again, this time for his final gambit of

the Kaiserschlacht – against Paris from the Aisne.

The battle of the Lys was a turning phase

of the war. The Germans won tactical victories but failed strategically. Their

armies were showing fallibility, and the innovative shock tactics were

regressing to attritional warfare as a result of the high casualties they were

suffering. Foch was growing into his role as Allied supremo, and had acted

decisively and with resolve in the later stages of the battle.

At the close of Operations Michael and

Georgette the Germans retained their numerical superiority on the Western Front

– 208 Divisions ranged against 168 – but they had been badly damaged, and many

of their best units had been sacrificed. Most worryingly for Ludendorff he now

had nowhere to look for reinforcements from the East, whereas from the West,

American troops were beginning to arrive in numbers. His Kaiserschlacht was to

have one more roll of the dice.

* The battle of Kemmelberg, as a distinct departure from Operation Georgette's original conception, is also frequently known as the Fourth Battle of Ypres

No comments:

Post a Comment