|

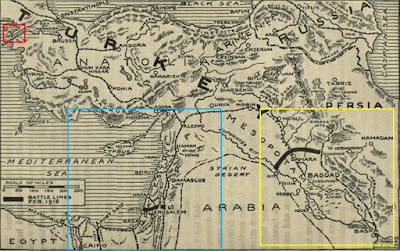

| The campaigns to break Turkey, hence the central powers: red Gallipoli (later Salonika) red; Sinai and Palestine blue, and Mesopotamia yellow. |

We have seen how Maude entered Baghdad in triumph on 11th March 1917 (see Post 3/2/17) having forced his way from the south via Kut. It put him in control of the hub of all important communications in northern Mesopotamia (Iraq). Besides the main waterway, the River Tigris, it included the southern terminus of the Kaiser's pet project - the Berlin to Baghdad railway (see Post 3/11/15). In fact, the track northbound to Turkey had been laid only as far as Samarra, also on the Tigris, 100 miles upstream, making Samarra itself an important railhead. Telegraph lines and decent roads fanned out west, north and east from Baghdad. In particular a major highway ran to the north east following the course of the River Diyala (a large tributary of the Tigris) as it rose to the mountains and the Persian plateau. One hundred or so miles further east lay Hamadan, the advance garrison of the Russian Caucasus army, commanded by General Nikolai Baratov. Baratov was

|

| Nikolai Nikoleivitch Baratov |

|

| Part of Maude's famous but slightly disingenuous proclamation. |

Thus, far from having time to celebrate and enjoy his new position of authority as ruler of the Baghdad vilayet*, Maude faced intensification of his operations. He contented himself with a diplomatic proclamation, posted throughout the vilayet, portraying his forces as liberators of the Arab peoples to ensure safety of their culture and customs. Trusting that this would keep the local people and factions onside, at least for the time being, Maude set about organising his forces into four separate groups.

The first had the

greatest challenge – that of moving north east to link with Baratov. This group

comprised two Indian Brigades under command of Maj-General Kearney. Success

here might trap the Turkish 13th Corp (6th Army), a

strong force that in the heady days post Gallipoli and Kut euphoria not only

threatened southern Mesopotamia but also routes through Persia to India. To the

west of Baghdad a smaller group rapidly took control of Feludja by 19th

March, though just too late to cut off large numbers of troops retreating along

the Euphrates. The other two groups were to push northwards to Samarra, one on

either bank of the great Tigris river. On 13th April both groups

began their advance in scorching heat. They were opposed by the Turkish 18

Corps (6th Army) and fierce fighting ensued. In three days they

advanced nearly forty miles on the right (western) bank, though less so on the

left.

Kearney’s brigades

left Baghdad for the mountains of Jebel Hamrin and the Persian plateau on 15th

March. They made good progress and within a week had captured key towns of

Buhriz and Baqubah along the river, and had reached Shahraban (today

Miqdadiyah), halfway to their rendezvous. Baratov had broken out gamely from

his garrison and his cavalry was at one point in Kermanshah, less than 100

miles away. Unknown to him (or the British) the revolution in Russia was

resulting in breakdown of discipline, planning and supply lines. Sadly, he could

get no further before being forced back. The 13th Turkish corps

meantime, sensing a tightening noose, had pulled back and skilfully organised

new defences on the higher ground of the Jebel Hamrin hills in front of

Kearney’s advance. What followed is sometimes known as the Battle of Mount

Hamrin. Sorties raged through the day of 25th March. Both sides lost

heavily, the British more so, such that they could not prevail and broke off

the action. The Turks conducted a managed retreat to the north to link with

other elements of the 6th Army. They had escaped, but would not

threaten Persia or Mesopotamia again. Kearney skirted round to the south and

continued east, eventually meeting up with some Cossack advance guards on 2nd

April. However, once he recognised the reduced state of the Russian forces, and

the lack of threat from the Turks, Kearney turned to re-join Maude’s main

groups.

|

| A British gunboat on the mighty River Tigris 1917 |

The Tigris twin prongs of the

advance on Samarra were making steady progress. On April 7th, a

counter attack came from the east (from some of those withdrawing from Mount

Hamrin) and held them up for nearly a week, but on 24th April 1917

Maude’s forces entered and captured Samarra, taking 700 prisoners, large

artillery and several locomotives in the process.

Maude's achievements as the Commander of the Mesopotamiam army were considerable. He was regarded by the top brass as something of a plodder, and was give the odd – and unflattering – nickname of ‘Systematic Joe’. It seems to me that he conducted mobile warfare in testing conditions far more effectively than some of the big names on the Western Front. Despite lukewarm support from the CIGS in London, Sir William Robertson (who wanted nothing to detract from Haig’s agenda in Flanders), he continued to make ground with notable victories, taking ground in the west at Ramadi, and to the north at Tikrit. Then suddenly in November he was struck down with cholera, and died – bang, just like that. Ironically he died in the same house as the German Marshal von der Golz, who had died there in occupation eighteen months earlier. Maude is buried in a Baghdad war cemetery, but there is a memorial to him in the Brompton Cemetery in London. I fully intend to seek it out and pay my respects.

*vilayet - an Ottoman administrative district

Fascinating stuff Sean! My grandfather Major Peter D'Souza was with Kearney in the Medical corps. He got to Baghdad where family legend has it that, while caring for injured captured German officers, he overheard them planning a future war and reported it. Apparently they did not realise he was a linguist who understood spoken German.

ReplyDeleteThanks Mike, a great story. Presumably they were planning Poland first next time?

Delete