|

| Russian Empire pre World War 1 |

The primitive feudal economy of the Russian

Empire, in place since its creation in 1721, began to change in the 1860s with the abolition of serfdom and tentative

moves to respond to the industrial modernisation sweeping Western Europe.

Urbanisation and industrialisation developed but brought with them social

unrest and a weakening of the autocracy. By the early 20th century industrial

unrest and crippling strikes were frequent. The war with Japan in 1904, alongside tensions with Germany, the Balkans and the Ottomans, contributed to nearly

twelve months of revolutionary turmoil through 1905. This was eventually

suppressed, but at the cost of the Tsar agreeing to an elected parliament – the

Duma – plus certain civil and trade union rights.

|

| Alexandra Fyodorovna. German born grand-daughter of Queen Victoria. |

As we have seen, Russia’s war to date had

been a dismal one (Posts 18/1/15; 23/1/15; 7/6/15 and 28/6/15). Pervading gloom was lifted only right at the start – with

Lemberg and the crushing victories over the Austrians in Galicia (Post14/1/15) – and in mid

1916 with Brusilov’s counterstroke (Post 15/5/15). They also clutched at the perennial hope that

Allied victory against the Ottomans would hand them Constantinople. After the

disastrous defeats of 1915, Tsar Nicholas had appointed himself as supreme

commander of the army, replacing his own uncle, the Grand Duke. He was now

directly accountable for for failures and by late 1916 his reputation had hit rock

bottom. In the battlefields, Brusilov’s surge had degenerated into costly

attritional warfare. At home the Tsarina Alexandra’s court was rumoured to be

full of bad influences (foremost amongst them Rasputin) and German agents. The

Tsarina was hated by the common people, while the Tsar had lost all trace of

respect.

|

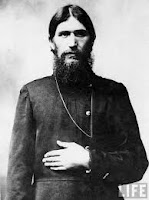

| Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin |

No comments:

Post a Comment