The soubriquet ‘Nivelle’s Offensive’

includes the Battle of Arras, covered in the preceding post, but its infamous

connotations rest with his own main battle – the Second Battle of the Aisne. We

have already covered Nivelle’s extraordinary rise to the top of the French

military tree (See Post 18/4/17).

His decline started almost from the moment of his appointment by Prime Minister Briand in December 1916, and ended even more precipitately, with a posting to Africa less than six months later. From the outset the misgivings of more experienced generals about his plans led politicians to doubts, and Nivelle found himself having to justify his confidence repeatedly. At one point he offered to resign, and his ‘back me or sack me’ tactic held off the doubters - that, and his undertaking to call it off if not decisive in 48 hours. However, matters took a serious turn when Briand’s patched up government fell apart in late March.

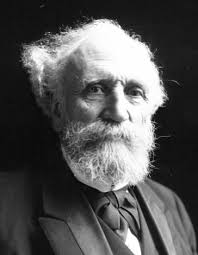

The new premier was

Alexandre Ribot, a brilliant academic taking his second bite at the prime

ministerial cherry (his first had lasted only a few days, coming just before

the outbreak of war in 1914). He chose a fellow academic as his Minister for

War, Paul Painlevé, an extraordinary man – dazzling mathematician; first passenger in

an airplane in France (piloted by Wilbur Wright in 1908), and subsequently

prime minister three times himself. Painlevé’s

studious approach rubbed up against Nivelle’s bravado, and was much more in

tune with that of his friend General Philippe Pétain. These frequent challenges (added to the detailed

rehearsals that were a feature of Nivelle’s planning, and the loss of documents to German

trench raids) undermined security seriously. It was later said, darkly, that by

the time the offensive began in April, every waiter in Paris knew the details

of Nivelle’s plans.

And so the prelude

to this particularly French drama began on 6th April, with the

artillery drum roll along more than fifty miles of front. The civilian

populations of Reims and surrounding villages were evacuated in anticipation of

zero hour on 14th April. Incredibly, bad weather supervened yet

again. Snow (does anybody seriously doubt global warming) – postponed zero

hour to 6am on 16th April when once again, droves of brave French

infantrymen crossed the parapets.

His decline started almost from the moment of his appointment by Prime Minister Briand in December 1916, and ended even more precipitately, with a posting to Africa less than six months later. From the outset the misgivings of more experienced generals about his plans led politicians to doubts, and Nivelle found himself having to justify his confidence repeatedly. At one point he offered to resign, and his ‘back me or sack me’ tactic held off the doubters - that, and his undertaking to call it off if not decisive in 48 hours. However, matters took a serious turn when Briand’s patched up government fell apart in late March.

|

| Alexandre Ribot Prime Minister 1917 |

The first Battle of the Aisne, fought in

the breathless days of September 1914, when the German juggernaut had been

reversed by the Battles on the Marne to the south (See posts 27/12/2014 and 30/12/2014),

had signalled the start of trench warfare. The Germans had retreated until they

found near impregnable positions on high ground to the north of the River

Aisne. This had then led to the efforts to outflank each other that became the

race to the sea. Three years and millions of casualties later, the German

positions had become, if anything, more formidable, and yet Nivelle saw this

part of the front as suitable for the breakthrough that would roll up the

German armies in the Noyon salient, starved of communications.

The 1914 battle had taken place in

crossings of the river and up the steep northern slopes, predominantly between

Soissons and Berry-au-Bac. This time the attack was on a wider front (of over

50 miles) from Laffaux in the west to Monvilliers, north east of Reims, and its

centre of gravity was further east (see map). But the aim remained to capture

the high ground along the Chemin des Dames, and to break through the Craonne

plateau and to the plain of Laon, heading north towards Haig and Franchet

d’Esperey’s forces at either end of the Siegfried line.

Nivelle’s grand victory plan involved reorganising

his army groupings to create a central group under General Micheler. Micheler replaced the sceptical Pétain who was promoted sideways (not for long). The central group had

four armies, each under command of a Nivelle devotee. From west to east these

were: the 6th, under his enforcer Mangin (Vauxaillon to Hurtebise);

the 5th, under Mazel (Hurtebise to Reims); the 4th, under

Antoine (east Reims to Moronvilliers), and the 10th, under Duchesne

(in reserve). The plan required Mangin and Mazel to strike hard on day 1, and

on day 2 for Anthoine to launch from the east against the stretched German

flank. Not since the Marne had the Germans been attacked on such a wide front.

Nivelle’s expectation was they would already be seriously weakened by Haig’s

assault at Arras and another attack by Marne veteran general Franchet d’Esperey

at St Quentin, the southern end of the Siegfied line.

A bold, grand plan it may have been, but it

was riddled with flaws and doomed from the start. Firstly, although Haig’s

forces did well at the northern end of the Siegfried line, Franchet d’Esperey

could make no impact at the southern end. Secondly, as mentioned, the Germans

were prepared for every move and gambit. Thirdly, Nivelle and his generals

(Mangin in particular) made completely unrealistic demands of their already

weakened and demoralized troops, paying little regard to the difficult terrain

and fortifications they would have to overcome. Likewise with tanks, Nivelle

committed the bulk of France’s force to unsuitable terrain althoguh, unlike the

poilus, the new Schneider tanks were untested and unreliable. Fourthly, and unforgivably,

Nivelle had no appreciation of the strength of the German positions. Like

Rawlinson at the Somme, he assumed that the weight of his attack would overcome

any obstacles with ease. When warned that Germans were moving reinforcements to

anticipate his attack, he responded that the more Germans there, the greater

the victory – astonishing with the experience of the Somme first day only months earlier; unbelievable, with 100 years hindsight. Especially on the chalky

heights above the Aisne, the Germans had utilised all of their defensive

ingenuities in strengthening well know defensive positions, including the Forts

at Malmaison and Brimont. Churchill wrote of this state of affairs:

"So Nivelle and Painlevé found themselves in the

most unhappy positions that mortals can occupy: the Commander having to dare

the utmost risks with an entirely sceptical chief behind him; the Minister

having to become responsible for a frightful slaughter at the bidding of a

General in whose capacity he did not believe, and upon a military policy of the

folly of which he was justly convinced. Such is the pomp of power"

|

| Paul Painleve War Minister 1917 |

Even at this stage, the French army was a

formidable force and, with determination and weight of numbers, expensive gains

were achieved at many points of the battlefront although at no stage was the

strategic breakthrough close. In summary, day one saw little or no

progress for Mangin’s forces on the left. In the centre, Mazel made progress

around Craonne and pushed upwards towards Ville-aux-Bois, a gateway to the

Craonne plateau. On 17th, as planned, Anthoine’s 4th army

began its two pronged assault on Moronvilliers at the eastern end (right) of

the front. Modest gains were made into the woods. On the 18th, the

persistence of Mangin’s troops saw progress on the left to the heights of

Aizy-Jou, finally flattening out the German salient in Missy-sur-Aisne. Small

advances were made to the east, including capture of the main Reims-Laon road

towards Corbeny. Four days in – double Nivelle’s own deadline – it was clear

that no strategic breakthrough was possible. The French public, informed by the

press, was in despair at the dashing of high hopes created by Nivelle. For

nearly three weeks the fighting continued, justified by piecemeal gains here

and there. Anthoine’s men fought heroically on the Moronvilliers heights, gaining

ground but no significant advantage. In the government the wildly exaggerated

casualty figures were causing near panic. By the end of April time had run out

for Nivelle. Pétain was installed to the position of Chief of General Staff at the War Ministry (in waiting to

replace Nivelle) and Haig was given permission to develop his plans for Ypres. Increasingly

desperate, Nivelle made Mangin - his loyal ally - scapegoat for the failed

breakthrough on the left, and removed him from command. Still the fighting went on, and still the French gained slowly, but as it ground

towards a standstill, Nivelle was invited to resign on 15th May. He

refused, but was promptly fired and replaced by Pétain. By 20th

May the furthest point of advance was reached, and tactical counter-attacks by

the Germans suggested that they would concede no more ground. By this point,

the French held all of the Chemin des Dames, and had pushed the German line

back appreciably to the north of Reims (see map - green line is the Chemin des Dames).

However, Pétain had inherited a desperate position. The first reports of mutiny

in the reserves came at this moment. Infantrymen in scores refused to advance

to the front to become more cannon fodder – who can blame them? Rumours spread

quickly, both to the front line and to those reserves waiting on the outskirts

of Paris. The month that followed showed Pétain at his finest, even surpassing his achievement at Verdun. By

visiting and speaking personally to officers and men in over 100 Divisions he

dispensed a blend of concessions, discipline and inspiration that converted

feverish unrest to resolute acceptance. And unlike Nivelle, he and his

advisers managed to keep the lid on the scale of the problem, and the Germans remained unaware. The risk of revolution had passed by the end of June, but there would

be no more French advances in 1917. The British army now carried the Allies’ hopes

for breakthrough – to the north, in Flanders.