|

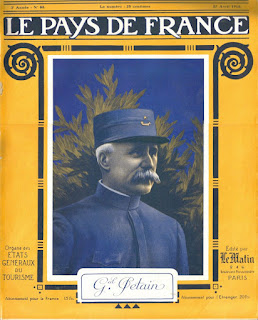

| Gen. Henri Philippe Petain. "Courage - on les aura!" (Courage - we'll get them!) |

Of all the fortifications, in their concentric rings, protecting Verdun, the elevated plain of Douaumont with its 'impregnable' fort was the greatest. It was symbol itself of symbolic Verdun, to the French people if not to Joffre. Its great subterranean garrison, capable of holding 1000 troops, held only 500 at the start of February, and by 25th was held by only 50 part time irregulars. Its capture on that day provided Germany's greatest morale boost of the campaign, and a major challenge to the French spin doctors. Otherwise this second phase provided more hard won gains for the German, but the pattern of valiant French resistance and high casualties on both sides was becoming established.

Petain became the embodiment of France's determination to hold - "Tenir!"

The heroics of Driant and his men had held up the whole of General Schenk's 18th Army Corps to such an extent it took Schenk two days to gain two kilometres of ground - despite the pulverising preliminary barrage. By the 25th the French, although holding their line, were at the point of collapse. However, the German vanguard was almost exhausted by the violence of the French defence, and it was here that Falkenhayn's risk in leaving large reserves on the other parts of the front, lost him the decisive breakthrough.

|

| German heroes of the 24th Brandenburgers, who captured Douaumont almost by chance. |

However, they could not take the redoubt to the east, or the village of Douaumont itself to the west, so the line held – just – at the end of 25th.

On the left bank, attacking between Bethincourt and Forges the Germans advanced slowly, and took the the villages of Forges and Regneville before being repulsed by the French and pushed back into Corbeaux Wood. In another two days they regained the wood and pushed to the lower slopes of Goose Hill leading to Mort-Homme. The village of Cumieres was a focus of particularly severe action and changed hands more than once. To the east, the fierce German assaults on the slopes of Vaux and its fort were resisted. None of these small gains provided the Germans with the morale boost to match the capture of the Douaumont fort.

On that day, Castelnau arrived to take charge of the overall defence, and the next day Petain arrived by car, ahead of his 2nd Army. Pétain’s arrival was timely. Over the previous five days the French line had been pushed back over four miles. On Saturday 26th a counter attack was launched, and the 20th Corps of Nancy, led by Balfourier, pushed the Germans off the Douaumont plateau, except for the 80 Brandenburg men who remained locked inside the fort. Balfourier’s achievement marked the ending of this first and most critical phase of Verdun, focused as it was on Douamont and the surrounding high ground. The Germans did try one more outflanking movement to the east. Having failed to dislodge the French from Eix and its surrounding heights, they moved on the village of Manheulles, six miles to the south. They were attempting to gain artillery access to the French southern line of supply, but they did not succeed. The topography and the communication lines were more difficult for them, and they did not try again.

The valiant, skilful French defence and withdrawals had exacted heavy casualties, and forced the Germans to pause for a few days of relative quietude, and reconsider their plans. They determined to broaden the assault, involving a major offensive on the left bank, with the high ground of Mort-Homme as the main prize. They would also persist further from the north east on the right bank against Vaux.

The valiant, skilful French defence and withdrawals had exacted heavy casualties, and forced the Germans to pause for a few days of relative quietude, and reconsider their plans. They determined to broaden the assault, involving a major offensive on the left bank, with the high ground of Mort-Homme as the main prize. They would also persist further from the north east on the right bank against Vaux.

The German forces were thus split into two groups, NE and NW, and they would spend the next few weeks throwing themselves against the corresponding parts of the salient. Each had a new commander, and the Crown Prince Wilhelm was pushed into something of a back seat. They renewed their assaults in more traditional pincer style between 6-8th March, and the fighting resumed its full ferocity.

|

| Tenir - 'hold!' French poilus in early days of Verdun. Note the shallow trenches. |

On the opposite side, the French defence had been invigorated by the arrival of Pétain. He immediately organised his line of defence into four sectors;

and his forces into four concentric groups corresponding to the sectors. He

greatly strengthened medium and heavy artillery positions in the four levels of

retreat. He planned and began to implement the policy of tourniquet (literally 'turnstile'), which rotated the frontline troops every few days to ensure at least some rest and relief (a very relative concept). He also set about fortifying

the road supply line from Bar le Duc, for food, weapons and men. This became

immortalised as the Voie Sacrée. With the

blockade of the main railway lines north and west of Verdun it would prove the

only route to keep supply lines open. Above all, Pétain inspired confidence and resolve amongst the troops. On 10th March, Petain addressed his men:

"For three weeks you have withstood the most formidable attack which the enemy

has yet made. Germany counted on the success of this effort, which she believed

would prove irresistible, and for which she used her best troops and most powerful

artillery. She hoped by the capture of Verdun to strengthen the courage of her Allies

and convince neutrals of German superiority. But she reckoned without you! The

eyes of neutral countries are on you. You belong to those of whom it will be said:

"They barred the road to Verdun."

"For three weeks you have withstood the most formidable attack which the enemy

has yet made. Germany counted on the success of this effort, which she believed

would prove irresistible, and for which she used her best troops and most powerful

artillery. She hoped by the capture of Verdun to strengthen the courage of her Allies

and convince neutrals of German superiority. But she reckoned without you! The

eyes of neutral countries are on you. You belong to those of whom it will be said:

"They barred the road to Verdun."